Repost from The Conversation. Published August 20, 2020.

By Chris Barrington-Leigh, Associate professor, Health and Social Policy and the School of Environment, McGill University, and Adam Millard-Ball, Associate professor, Environmental Studies, University of California, Santa Cruz.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, cities around the world are rediscovering the value of walkable and bikeable streets. From Oakland, Calif., to Amman, Jordan, cities have restricted driving on certain streets in order to create space for socially distanced physical activity. Other cities, like Bogotá and Berlin, have scrambled to convert car and parking lanes into bike lanes in response to the precipitous drop in public transit ridership.

Street networks are about resilience, whether to the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change or even a future with autonomous vehicles. Neighbourhoods with well-connected streets can evolve into more walkable, complete neighbourhoods or denser settlements as needed.

The COVID-19 response shows how quickly a city can move to repurpose street space in the short term. Traffic cones, planters, paint and signs are all that is required. The market for bicycles has ballooned just as fast.

In the long term, however, the skeleton of a city — the connectivity of its street network — is a permanent constraint to walkability and bikeability. New bike lanes and pedestrian space will have little impact where a city’s skeleton is not up to the task.

Connected streets

Street-network connectivity matters because it puts destinations within easy reach. In a disconnected, sprawling network typified by dendritic branches, cul-de-sacs and gated communities, a grocery store that lies a hundred metres away can be more than a kilometre on foot.

In contrast, the street grids common in Latin America provide direct routes for pedestrians and cyclists, as do the irregular but connected networks of pre-industrial European (e.g. Vienna) and Asian (e.g. Nagoya) urban cores.

Street-network sprawl matters little to car drivers, but is an indignity to those on foot. Not surprisingly, people with a choice of travel options respond accordingly. Building more connected streets (that is, less street-network sprawl) has reduced car ownership and increased walking in diverse geographic and cultural contexts, including Japan, France and the United States.

The rise of disconnected streets

Street-network sprawl, however, is on the rise almost everywhere in the world, according to a new index of street-network sprawl that we developed. We used data from OpenStreetMap, and our index covers every city and country on the planet since 1975. It presents a disturbing picture for future walkability in places where residential development could be set on a better course now.

The rise of cul-de-sacs in post-war suburban development in the United States is well known, but street-network sprawl has already peaked in the U.S. While new U.S. streets are still some of the most sprawling in the world, a modest decline since the 1990s reflects the efforts of cities and states, from Charlotte, N.C., to Seattle, to promote more connected patterns.

In the majority of the world, however, disconnected streets are becoming the norm, whether through tree-like branching networks in Tucson, Ariz., cul-de-sacs in Dublin or gated communities near Jakarta.

Maintaining connections

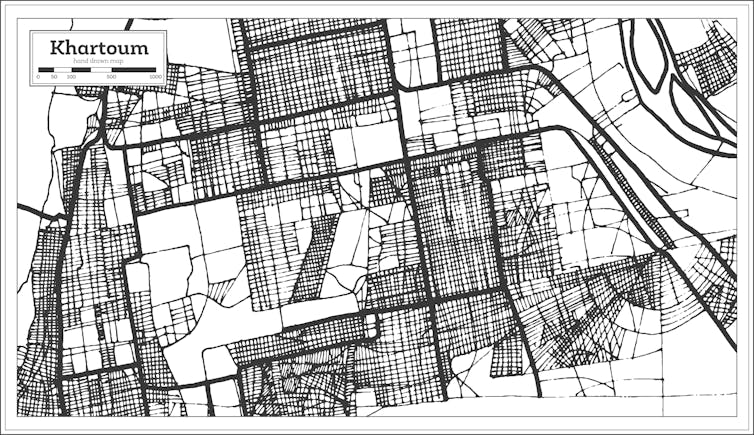

Where can cities that wish to turn around these trends look for inspiration? While in the minority, a range of places — Buenos Aires, Khartoum, Amsterdam and Tokyo, to name a few — have maintained a tradition of building connected streets.

Most importantly, these cities show that there are many paths to connectivity based on local traditions in architecture and urban planning, from a grid to an irregular pattern of three-way intersections. Dutch and Danish cities, meanwhile, show how to build cul-de-sacs for cars, while maintaining high connectivity for pedestrians and cyclists through cut-through paths at the end of each block. At the national level, China and Britain show how urban planning regulations can promote a fine-grained street network that is permeable to those on foot.

Street networks are a one-shot deal. After a new development is built, its streets are cemented in place for decades or centuries by the strictures of property ownership. Thus, forward-thinking regulations are vital to control long-run outcomes such as car dependence, energy use and greenhouse gas emissions. A coal power station locks in carbon emissions for 40 years, but the street network does so for centuries.

Urban resilience

Connected streets facilitate integrated communities, mixed housing types and easier access to services for those without cars, including our essential workers in times of unforeseen contingencies. Cities characterized by street-network sprawl, in contrast, are stuck forever in a suburban, low-density way of life.

The coronavirus pandemic has thrust on many of us an unsolicited but pleasant glimpse of life with quieter streets, cleaner air, pedestrian boulevards and an absence of long commutes. To realize long-term transformative change, cities must move beyond the surface and tackle their skeleton of new development.

With new standards and proactive regulations on the connectivity of new street development, they can put an end to street-network sprawl of cul-de-sacs, suburban mazes and gated communities, forging a path to resilient, equitable, healthy and clean urban existence.

Chris Barrington-Leigh, Associate professor, Health and Social Policy and the School of Environment, McGill University and Adam Millard-Ball, Associate professor, Environmental Studies, University of California, Santa Cruz

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.